Arts & Culture

By Lydia Woolever

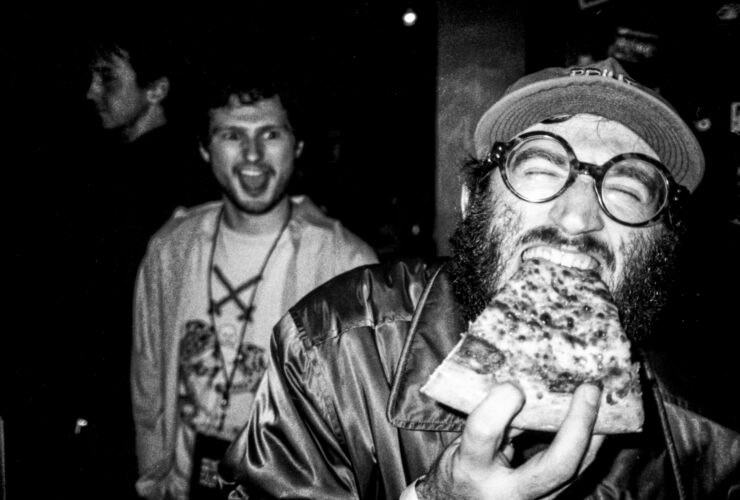

Photography by Alexis Gross

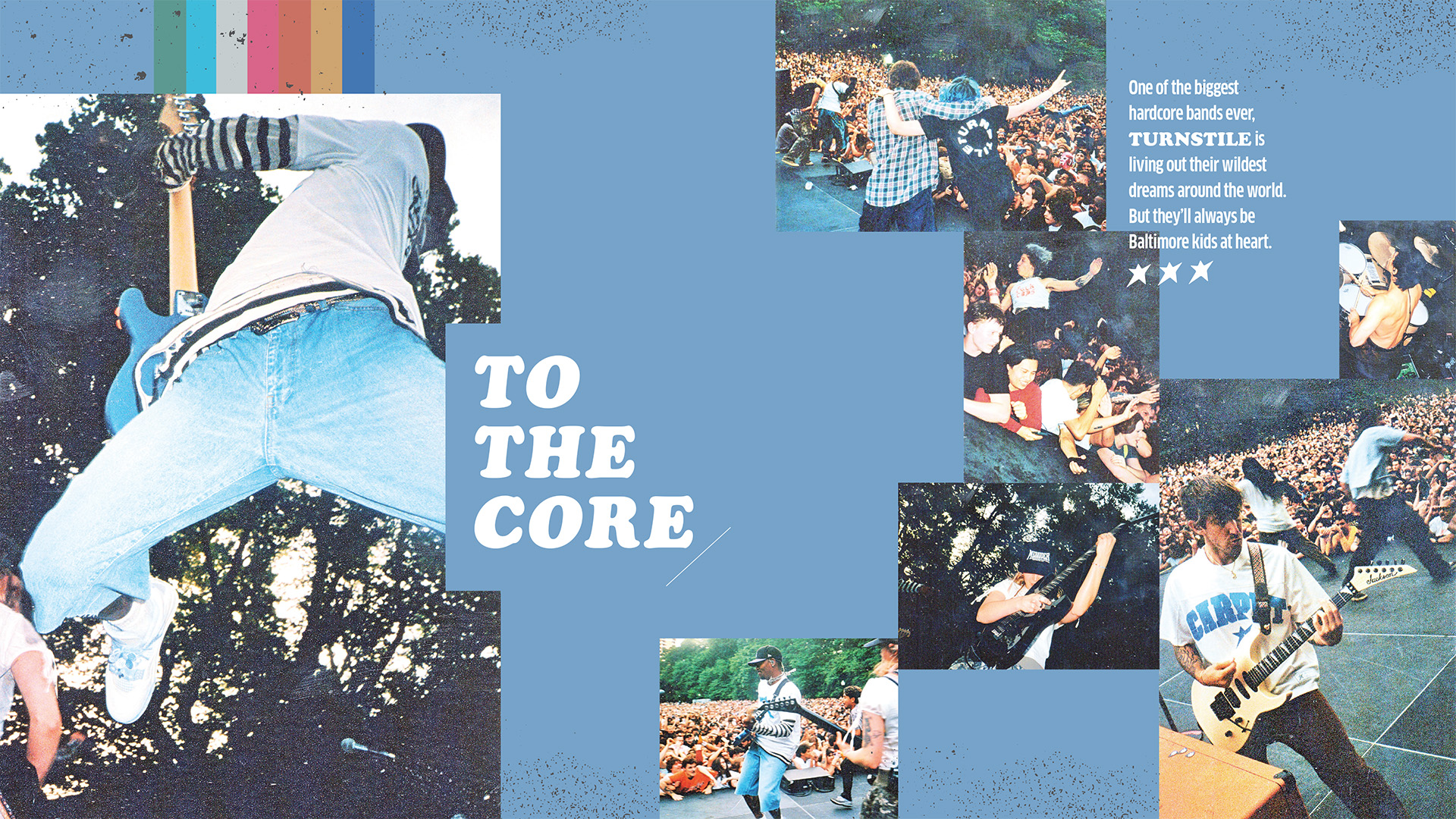

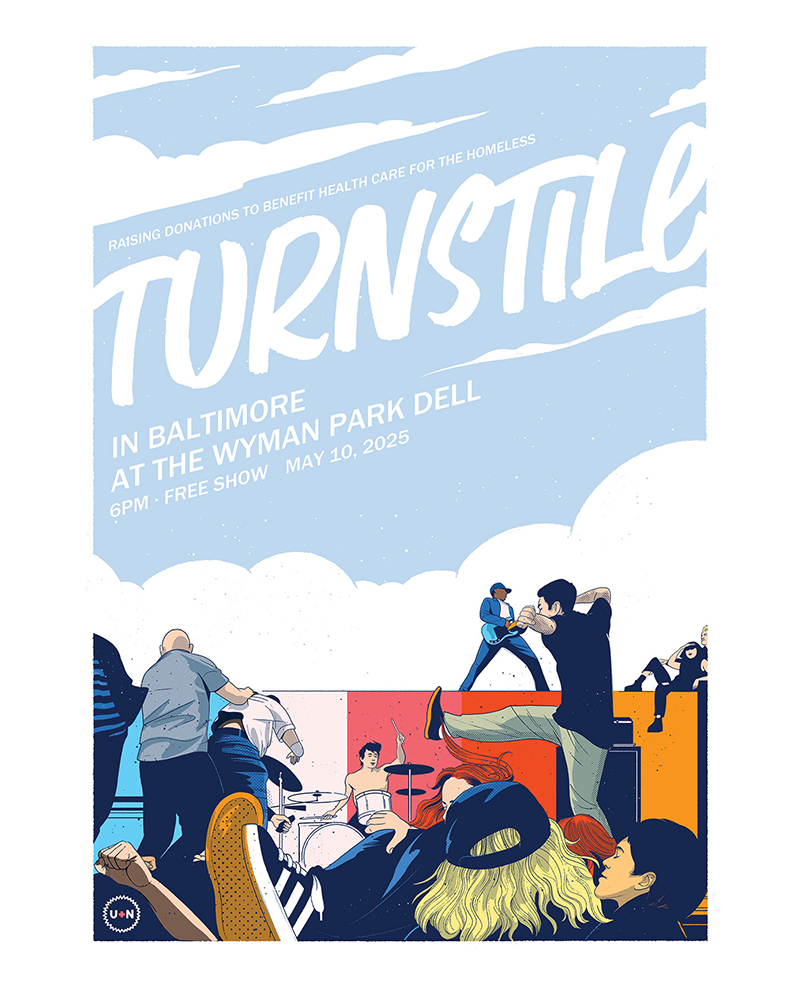

THROUGHOUT THE AFTERNOON, a crowd had been growing in the Wyman Park Dell. To the west, they scrambled down its hillsides beneath the Baltimore Museum of Art, cutting through brambles and over briars in search of a small clearing. To the east, they spread out across the grass and shimmied up oak trees for a better view near Charles Street. Looking south, there were people, and more people—old-head punks, fresh-faced Hopkins students, parents shouldering earmuffed babies—and high in the sky hung an almost-full moon, as if it, too, had been lured here, on this warm spring night in north Baltimore.

In the center of it all stood an empty stage, built there this very morning, its colorful paneled backdrop resembling those old off-air signals on early color TVs. And for a while, everyone waited there. Then finally, an hour before sunset, the first line of ambient synth began lilting out of those big, black speakers. A hush fell over the dell until, slowly but surely, Turnstile appeared.

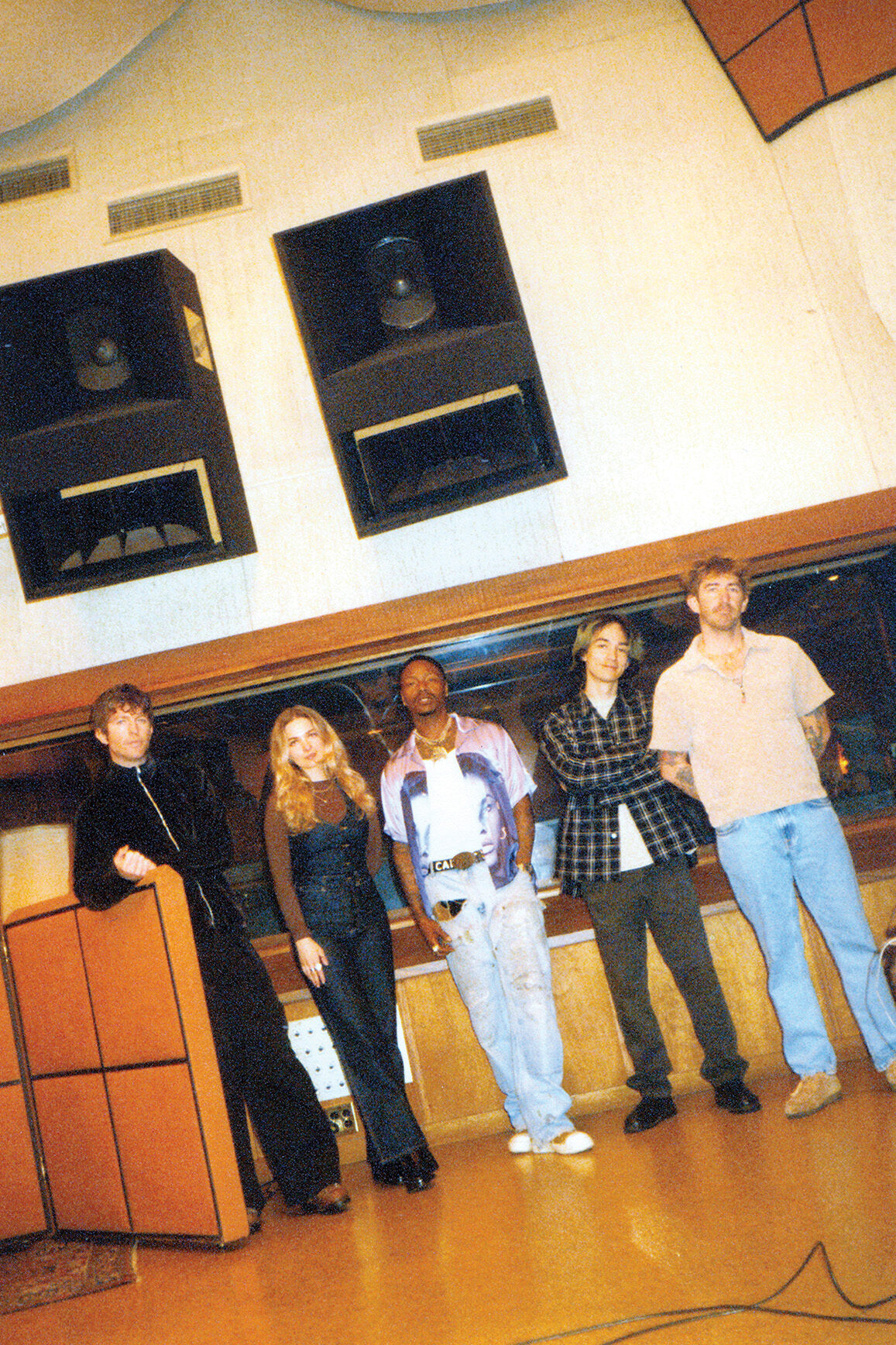

A single cheer swelled into an all-out roar as the band’s five members walked up onto the platform and took their places. Looking over the masses, lead guitarist Pat McCrory rubbed the back of his neck with a bashful smile, while bassist Franz Lyons went out to the front, waving with every inch of his limbs to the most faraway fans. With his hand on the mic, frontman Brendan Yates took a pause, and then in an almost a cappella tenor, let out the opening lyrics of the title track off their new album, holding the last note of each line until he couldn’t any longer.

Running from yourself now / can’t hear what you’re told ... Never let your guard down / anywhere you go...

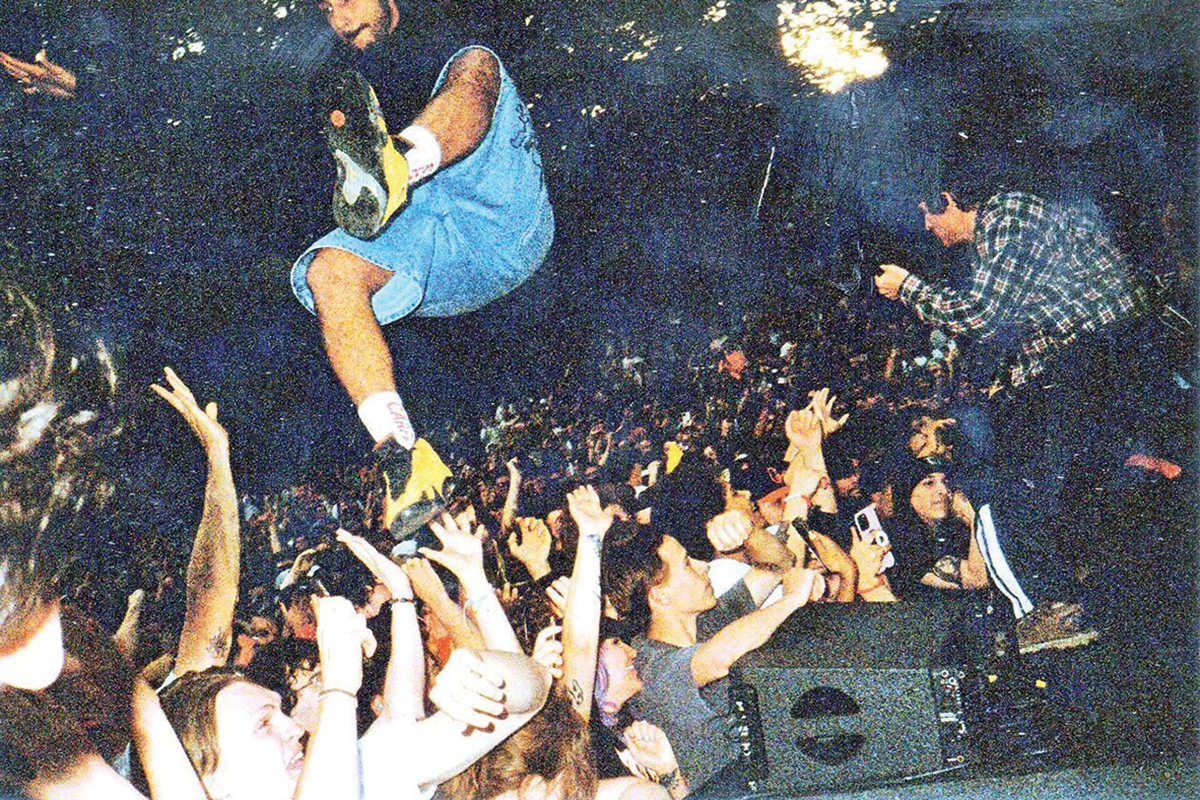

By now, a mosh pit had already swirled into formation and, before long, a procession of stage divers started lapping up around the band and leaping off with euphoric abandon into the open arms of strangers.

In the right place, at the right time / and still you sink into the floor...

Then everyone joined in the chorus.

It’s never enough / never enough / never enough / love...

TURNSTILE ON STAGE IN THE WYMAN PARK DELL THIS MAY. —ALEXIS GROSS

Ask anyone who was there: In that moment, something potent filled the air. Like the entire park was standing on the edge of a cliff together. Like the biggest band to come out of Baltimore in the last decade—maybe ever, and a hardcore punk one at that—was about to take a massive jump. And like they were bringing the city along with them.

Then Lyons, McCrory, and rhythm guitarist Meg Mills unleashed their first chords, drummer Daniel Fang dropped the beat with a thunderous punch, and the show truly began, transforming the dell into a billowing sea of bodies that didn’t stop moving for the next hour.

“All I could do was be grateful, like, the whole time,” says Lyons, remembering all the familiar faces. “I don’t know if that’s a feeling that could ever be replicated. And at the end of it all, it was just in our neighborhood.”

At one point, the band all lived nearby, and largely still do, except for Mills, their most recent addition, who resides in her native England. They know the best skateboarding spots. They have their go-to coffee shops. And they spent years imagining a free concert in this tucked-away green space. So with the help of friends, they finally hatched a plan, having no idea how many people would actually show up. Yates joked that it would be like a family gathering.

Which, give or take a crowd of 10,000, he says, “It was.”

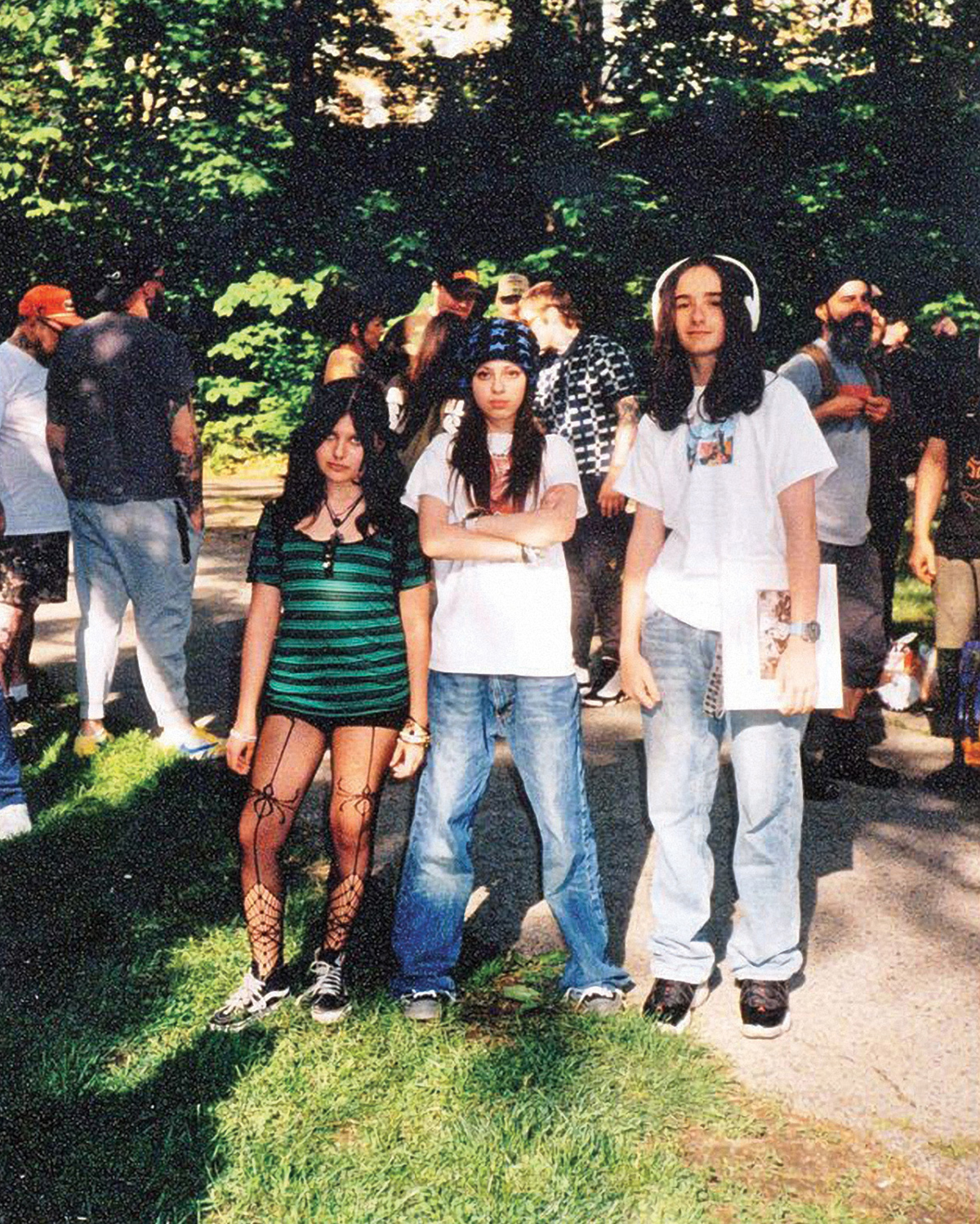

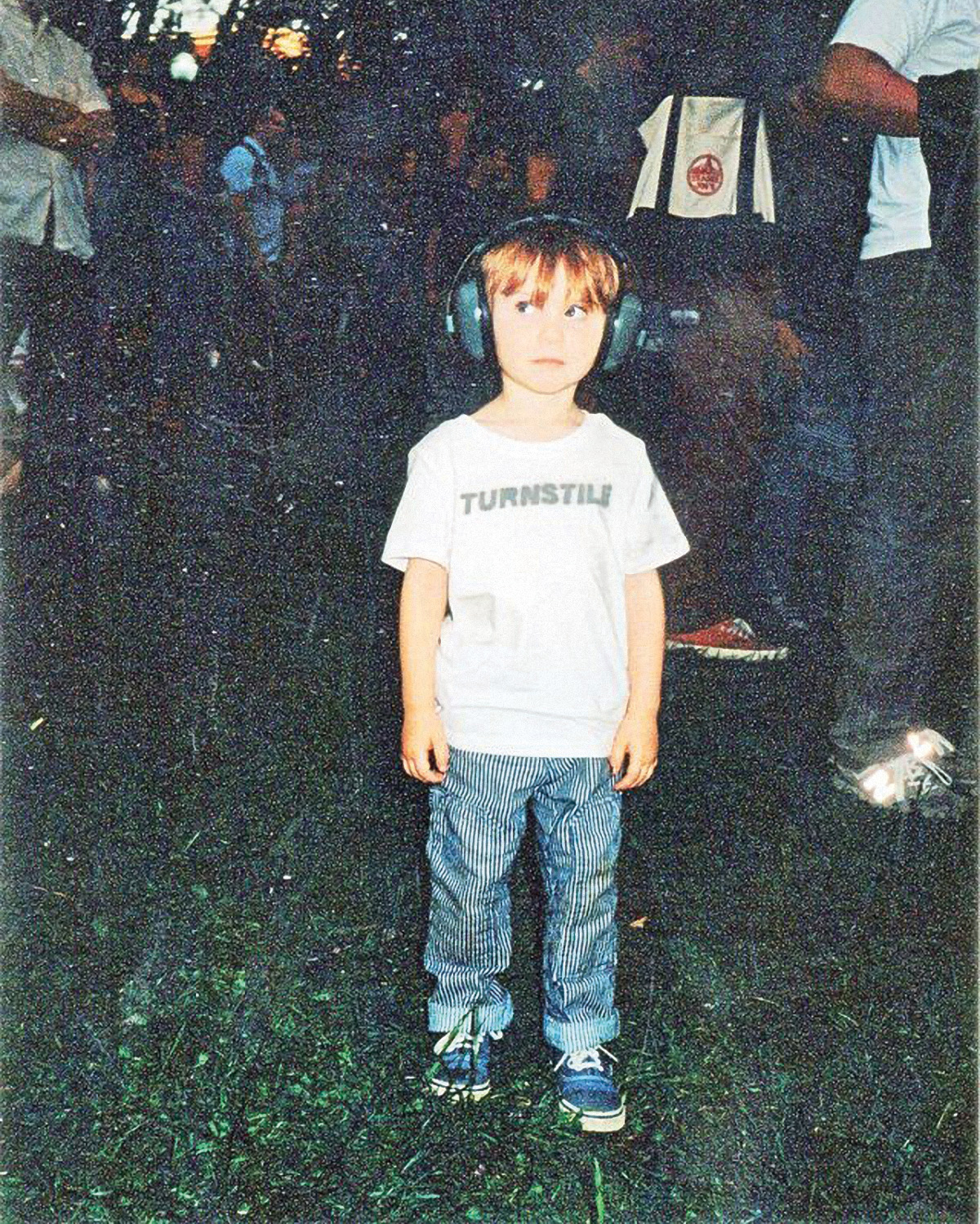

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: STAGE DIVING; PINT-SIZED FANS; MORE ATTENDEES IN CHARLES VILLAGE. —ALEXIS GROSS

A FEW MONTHS LATER, during a hot spell in August, Turnstile is back home in Baltimore, enjoying a brief respite before launching into the first leg of their new North American tour. They’ve already been across much of Europe performing Never Enough, the band’s fourth full-length album, which rolled out a few weeks after the Wyman show, to their greatest fanfare yet.

In the swirl of its release, they debuted singles on The Tonight Show, premiered a companion film at the Tribeca Film Festival, graced the cover of Pitchfork’s new print zine, and dropped a collection with their boys, the Baltimore-based fashion brand Carpet Company. By the end of the month, they’ll have topped the Billboard charts and recorded that NPR Tiny Desk concert—bringing their ever-evolving hardcore sound to legions of worldwide listeners. As pop-music icon Charli XCX predicted, this was “Turnstile Summer,” after all.

On the other side of that, the band is tired. They’re not kids anymore—being well into their 30s now, minus Mills (she’s 29). And most nights these days, Yates has been needing at least 10 hours of sleep.

“Dude, my concept of time is so warped,” says Fang. “Like all the stuff that we’ve done, all the shows that we’ve played, have just been so overstimulating—in the best way. I think we all knew we’d want to process the magnitude of how special this was. It’s a lot to catch up on.”

For the most part, they’ve been keeping it low-key: hanging at home, reading books, riding bikes, going for walks, seeing friends and family. Breaks like this are a sacred thing. Even after 15 years as a band, they still spend most waking hours together, including McCrory and Fang’s weekly game of Dungeons & Dragons. But they also revel in their alone time.

The other day, on his way to meet Yates, “I just found myself driving through our old neighborhood, looking at old places, feeling old feelings . . . and was like, you know what, I’m just gonna hang here for a bit,” says McCrory.

Being on the road all these years, he says, has kept “Baltimore in this perpetual honeymoon phase.”

Right now, many fans are finding Turnstile for the very first time, creating the illusion of overnight success. But they burst onto the national stage in earnest after their last album, Glow On, in 2021. And long before that, they were a bunch of kids firing up crowds from the DIY stages of Baltimore’s tight-knit hardcore scene. By the time they were garnering Grammy nods and opening gigs for childhood legends like Blink-182, they’d already been at this for over a decade. Which is to say, when they became “one of the most popular punk bands of [their] era,” per The New York Times, they were ready.

Everyone wants to know what happens next, after these scrappy stage divers go full superstar. But Turnstile knows exactly where they’re going. In large part because of where they come from.

“The biggest thing that Baltimore has given us,” says Yates, “is the grace and the space to find ourselves.”

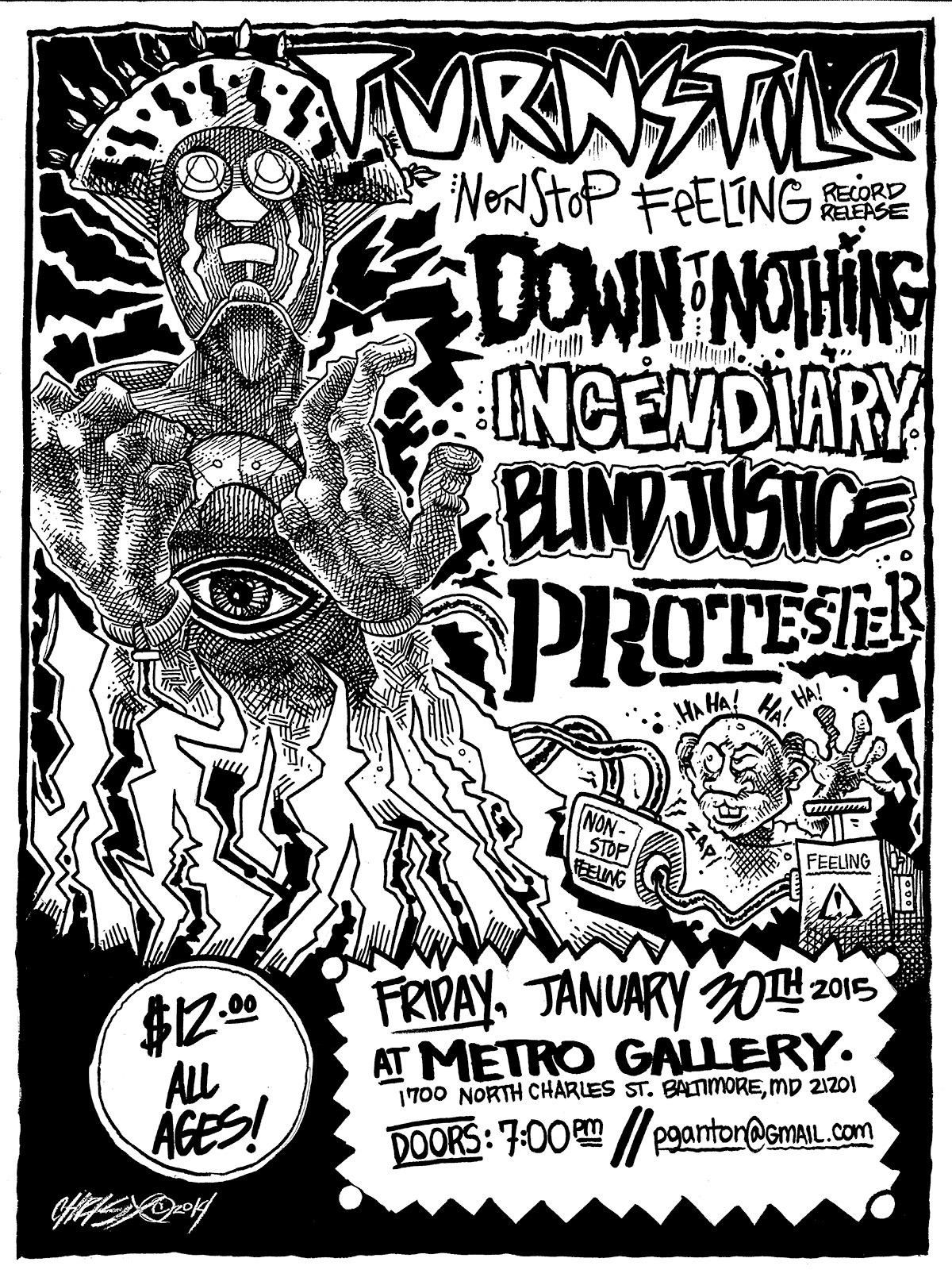

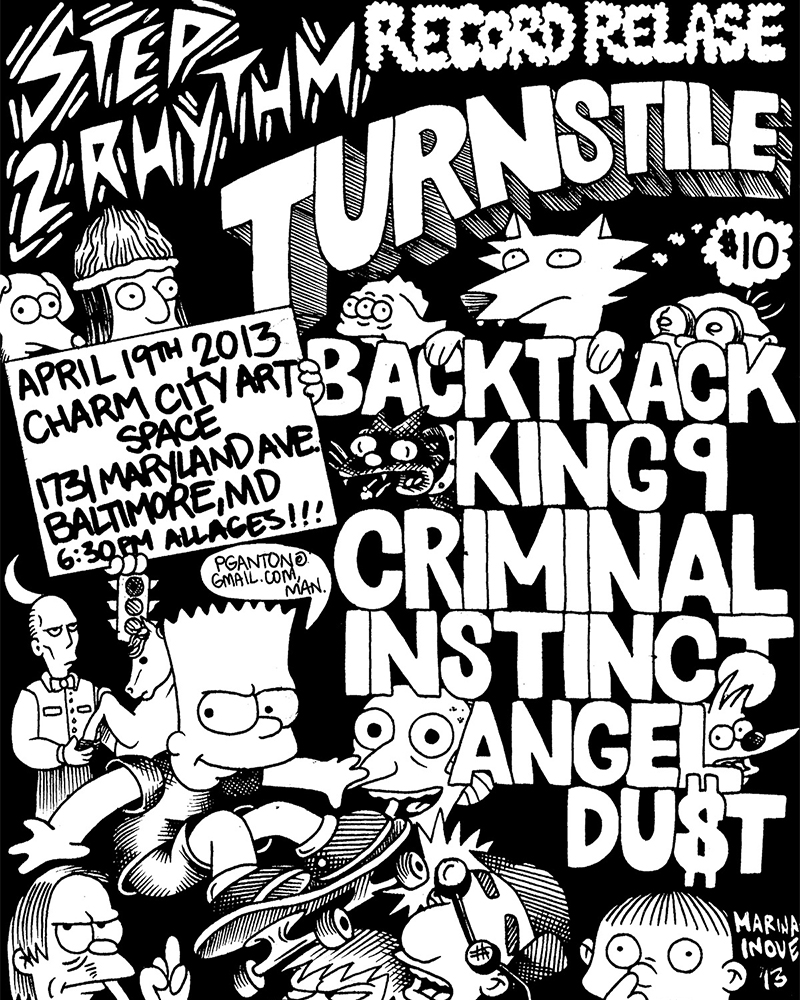

FLYER FOR NONSTOP FEELING RECORD RELEASE, 2015. —FLYER ART: CHRIS M. WILSON

YOU COULD MAKE THE CASE that hardcore was born just a few miles from Baltimore. In the late 1970s, as punk bands like the Ramones and The Clash gained commercial success, a new subgenre started brewing in American cities, including right down I-95 in Washington, D.C. There, a few District Heights kids formed Bad Brains in ’77—considered the pioneers of hardcore—and within a few years, Glover Park teen Ian MacKaye co-founded Dischord Records, helping launch some of the aggressive new sound’s most seminal acts: Minor Threat, Fugazi, even his old pal Henry Rollins, who went on to Black Flag fame on the West Coast.

Harder, faster, and more furious than its predecessors—full of artery-busting vocals, breakneck drums, and blistering guitars—this underground music was steeped in the spirit of self-determination. Often overtly political, it always gave the finger to corporate America. And with that anti-establishment, fiercely true-to-you attitude, its explosive live shows were the stuff of magic for certain outcast youth in the beltway suburbs.

“I think what’s so appealing is that it’s just very real,” says Yates, who grew up in Montgomery County, discovering local punk bands through mixtapes made by his older sister.

More than just passively listening, so much of hardcore is participating in this very physical, very human, very pure—when you think about it—act of self-expression, “letting out aggression, or experiencing joy,” explains the soft-spoken, often quite serious lead singer. “Throwing your body off a stage—while maybe people think it’s crazy, the feeling is so connected, to the music and to the immediate environment. You feel this trust that you can just fly, and that you will be caught.”

Yes, sometimes you might catch an elbow to the face in the process, but the chaos is catharsis. Even transformation.

That’s how it felt for Fang, who attended his first show at age 11. Like Yates, he became a fan through his older brother, who passed down CDs and filled the family computer with LimeWire downloads in Prince George’s County. Discovering Dischord helped him navigate the angst and isolation of adolescence, and he felt particularly drawn to the D.C. scene for its straight-edge ideology, do-it-yourself work ethic, and egalitarian community ethos. Throughout its heyday in the ’80s and ’90s, anyone could be a part of it. All you had to do was show up.

“I thought that was this bygone era that didn’t exist anymore,” says Fang, who, despite his blood-sweat-and- tears style of drumming, comes off as the band’s sweetheart. “[It] set an ideal, like, wow, things can be done this way. . . . Then finding it later in Baltimore was a full-circle thing.”

Before that, though, Turnstile’s story really begins in Yates’ middle-school basement. There, he started playing music with his neighbor, Brady Ebert. Those practices soon led to performances at local community centers and area churches. By high school, they were coming to Baltimore, where, in waves, bands like Gut Instinct, Next Step Up, and Stout had established the city’s rough-and-tumble hardcore scene, centered around its own particularly powder-keg sound.

It was intense and intimidating, at times breaking out in violence—and yet also surprisingly intimate. At hole-in-the-wall venues like Charm City Art Space on Maryland Avenue, shows were all-ages, and often dirt cheap, thus lowering the bar for entry. And on the floor or a propped-up sheet of plywood, bands of every skill level performed right in the thick of it, blurring the line between audience and artist. It was all a revelation for these young musicians. Not only did it now seem wildly possible to start a band. But the entire scene was also suddenly so simple.

BASSIST FRANZ LYONS PERFORMS WITH THE BAND, 2014. FRONTMAN BRENDAN YATES CATCHING SOME AIR AT THE CHARM CITY ART SPACE, 2014. —ELENA DE SOTO PHOTO

It was just “this collective, shared experience,” says Yates matter-of-factly. “And next time I’d see that person I was in the pit with, I would feel a sense of connection, even if I hadn’t met them yet. There’s this unspoken bond that forms over time. . . . Then before you know it, you realize you’ve made a lot of close friends.”

In those salad days, one especially formative friendship was Justice Tripp, an Essex musician in his late teens, whose crew took many of Turnstile’s future members under their wing.

“We kinda adopted Brendan,” recalls Tripp fondly. “We’d see him around and were just obsessed with this group of little kids—they were already super talented, and it was like, ‘Why are these children making music like this?’ Just smoking all the adults.”

After graduation, Yates moved north to attend Towson University, which is where he befriended Fang, dropping out shortly after. You see, Tripp’s band, Trapped Under Ice, was getting major buzz—quickly becoming one of the genre’s most influential new acts, evolving beyond its tough-guy brashness with deep grooves and dynamic melodies—and they were about to head out on a globe-trotting tour. They wanted him to come and play drums, his first instrument.

“It was my favorite band—and my peers, and my friends—asking me to join,” says Yates, which back then felt like being recruited by Metallica after The Black Album. It gave him permission to go all-in, and presented all kinds of worlds that could be imagined, “when the community around you is your biggest inspiration.”

Back home on break in 2010, he regrouped with Ebert and started working on new music. After teaming up with Fang—already a wunderkind drummer—they also looped in Lyons, another drummer, who’d hopped in the Trapped Under Ice van after a show in his hometown Ohio and now ran the Baltimore band’s merch. In this new outfit, he’d play bass, while Ebert handled guitar with another local friend, Sean Cullen. That put Yates on the mic, now as the frontman of a band named Turnstile.

“Pure energy.” That’s how Lyons remembers their first show in early 2011, when nerves kept him toward the back of The Sidebar on Lexington Street, then considered Baltimore’s own CBGB. It’s hard to imagine today, given his ecstatic, charismatic stage presence, at times almost defying gravity. But in this baptism by fire, his bandmates urged him on, as a small but amped-up crowd kicked around the pit and threw their fists into the air. Then and now, he says, “[We’re] gonna play like it’s the last thing we do on the face of this earth.”

That spring, Turnstile released their first EP on Myspace, Pressure to Succeed, followed by 2013’s Step 2 Rhythm, on Bandcamp—both brimming with rambunctious gut-punches that made their live shows barely last 20 minutes. It was around this time, as the band worked their way to the top of local bills, that fellow musician Paris Roberts first saw them.

“You literally just had to be there—everybody in the crowd singing every word to every song, moshing through the entire set,” recalls the Catonsville native and frontman for more recent Baltimore hardcore bands Truth Cult and No Idols. “It was an energy that didn’t stop. From the minute they set up, people just stage diving to the feedback, before they even started playing. Back then, you didn’t see many bands get a response like that except for Turnstile.”

That both intensified and took a turn after 2015’s full-length debut album, Nonstop Feeling. Following in the footsteps of Trapped Under Ice and other hardcore innovators, they started stretching the muscular edges of their early sound, revealing a band of musical polymaths with an ear for everything from punk elders like Madball and Agnostic Front to pop-leaning boundary-pushers like Tyler The Creator, Prince, and Beach House. After all, most of them came up on hometown heroes like Bad Brains, who infused their groundbreaking hardcore with reggae, and Rites of Spring, the progenitors of emo.

Loosening the genre’s grip even further, Turnstile now openly embraced those myriad influences, incorporating playful frills from hip-hop to surf-rock, while Yates’ punchy vocals drew comparisons to Rage Against the Machine’s Zack de la Rocha. All of which, of course, pissed off a few purists.

“But art constantly evolves,” says Tecla Tesnau, owner of Ottobar in Remington—one of Baltimore’s many venues with wide-ranging lineups, where the band was able to see first-hand how their city’s sound contained multitudes. “Did Picasso just stay in his Blue Period?”

By 2016, Pat McCrory completed the picture—the band’s clincher, if you will. The Carney native was already a good friend, being a fellow Towson alum and part of Tripp’s experimental follow-up, Angel Du$t, which has included multiple members of Turnstile. He joined on rhythm guitar after Cullen’s departure, blending seamlessly on their even more expansive follow-up, 2018’s Time & Space, which featured a surprise appearance from Diplo and was released via the Warner Music Group’s Roadrunner Records.

Back then, “It was like, alright, you knew these guys,” says McCrory, who exudes a disarmingly boyish charm and, according to friends, has a world-class sense of humor, “but now we’re gonna be together every single second—until the end of eternity.”

Turnstile was coming into their own, with each new record suggesting in real time both their impressive ambitions and increasing introspection. And then came that third album.

It’s a rare thing these days, in this era of solo prodigies, for a band to make it big, let alone a punk one. But in 2021, Glow On was Turnstile’s Nevermind moment, which in the ’90s catapulted both Nirvana and Seattle grunge into the mainstream. And while this new LP bottled that urgent fervor of their hardcore upbringing in Baltimore, its collection of newly lush, liberating, arena-ready anthems also gave them boundless appeal.

In an instant, they shot from underground royalty

into rock-music stardom: Think Rolling Stone hosannas,

Coachella stages, Converse collaborations, that Blink tour, and, of course, those Grammy nominations—four

in total, for “Alien Love Call,” “Holiday,” and “Blackout,”

twice. (In the ultimate flex, the band was even invited to

throw out an opening pitch at Camden Yards, with Mc-

Crory, a lifelong Orioles fan, fittingly doing the honors.)

But it wasn’t just snazzy riffs and state-of-theart production. On closer listen, you could also hear something else.

Take the opening track, “Mystery.”

There’s a clock in my head / is it wrong, is it right?

I know you’re scared of running out of time /

But I’m afraid, too

This was deep stuff, and they were not afraid to go there, exposing some of their (and our) most existential questions—about time, about the future, both the unknown and the inevitable. No wonder so many people, from scene faithfuls to curious newcomers, were now paying attention.

“I think it definitely changed all of our lives,” Yates told local arts writer Lawrence Burney in Pitchfork earlier this year. “But, simultaneously, it didn’t. . . . This band has existed for so long, we’ve just been doing the same thing, and constantly growing, and growing [in the] understanding of what we wanna do.”

Later in the album, another track is emblematic of that evolution. On the fever pitch that is “T.L.C.,” it’s all there—the classic pit-stoking choruses reminiscent of Trapped Under Ice days, the imaginative Sly and the Family Stone references showing off their amassed musical fluency, the Baltimore Club-suffused outro (with D.C. go-go beats also making an appearance elsewhere on the album—both a hat tip to the DMV).

“I want to thank you for letting me be myself!” shouted Yates, over and over, at the time seeming like a clever hook.

These days, it sounds more like a prophesy.

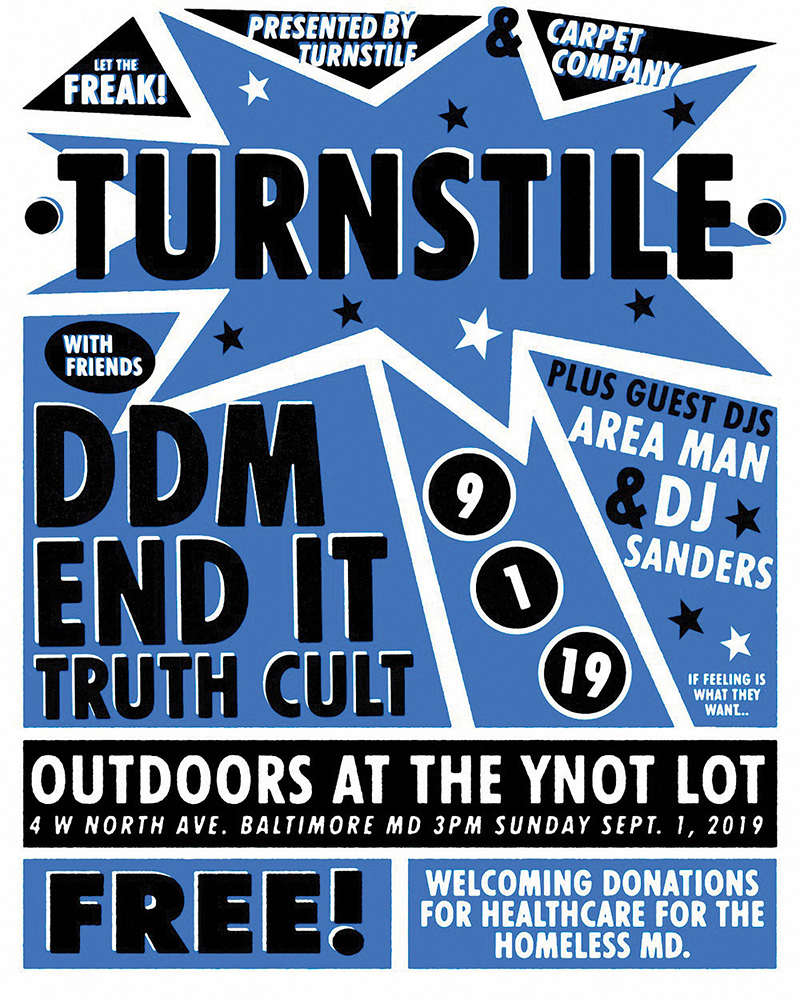

FROM LEFT: TURNSTILE FLYERS FROM THE FREE YNOT LOT SHOW, 2019; THE STEP 2 RHYTHM RECORD RELEASE SHOW, 2013; THE WYMAN PARK DELL SHOW, 2025. FLYER ART FROM LEFT: —ANDY NORTON; MARINA INOUE; ALEX FINE

ALL THE WHILE, back home, Baltimore was also undergoing big changes.

Over the years, its hardcore scene had ebbed and flowed. Bands broke up. Venues closed, with the loss of the Charm City Art Space in 2015 leaving behind one of the biggest voids. Turnstile was a buoy in the years that followed, luring their fans out of cramped basements into bigger pits like the Baltimore Soundstage, as well as carving out their own spaces through free outdoor shows at the Ynot Lot and Clifton Park Bandshell, often giving their opening slots to other up-and-coming local acts.

“How’s that saying go?” says Che Figueroa, co-owner of Baltimore-based hardcore label Flatspot Records. “A high tide lifts all ships.”

But the coronavirus pandemic would be the tipping point. As the live-music industry lamented its potential demise, a new generation of bands was about to boil over—Jivebomb, Sinister Feeling, Doubt, Erode, Gasket, Pinkshift, Fightback, the list goes on—channeling that pent-up energy into the next hot-blooded chapter of Baltimore’s hardcore legacy.

Right now, the scene is experiencing quite the renaissance, newly enriched with the omnivorous tastes and creative liberties of kids raised on the internet. Like End It—one of the city’s most in-demand acts, formed in 2017 and now dropping their debut album—recently covering both “Big Shot” by Billy Joel and “Could You Love Me?” by Maximum Penalty, a genre deep-cut.

“There’s definitely something in the air,” says their drummer (and McCrory’s old roommate), Chris Gonzalez. “After the lockdown, the shows were crazy. It was like, ‘Where did all these people come from?’”

And a whole crop of venues has been eager to greet them: Holy Frijoles, House of Chiefs, Ema’s Corner, the occasional skate park. In fact, Metro in Station North finds itself counting on hardcore shows, which are consistently packing rooms and drawing an increasingly diverse crowd.

Older dads, teen skateboarders, musicians from other scenes, people of color, lots of women, says Metro co-owner Emily Gordon. “Which is awesome to see, because when I was growing up, it was always boys, boys, boys,” she says—and mostly white ones. “Everyone is so positive and accepting these days. The general feeling is just excitement. People want to see what all the fuss is about. They know they’re in an important moment.”

That was undoubtedly part of the pull at Wyman Park this spring. At this point, Turnstile is big enough to play any stage in Baltimore, and for a profit at that. Instead, they stayed true to their roots: Not only was it a free show, with no barricade, and no sponsors beyond the band themselves, it was also a benefit, like the last few hometown stops before it, using on-site QR codes to help raise nearly $50,000 for Health Care for the Homeless.

“Those are all very crucial aspects of the hardcore punk ethos,” says Mike Riley, co-founder of the Charm City Art Space. “It’s always been much more about how you operate than how you sound.”

Though announced only a week in advance, planning for the show started back in January, with upward of 70 people playing a part, including veteran organizer Dana Murphy of Unregistered Nurse Booking, who worked closely with city officials, neighborhood associations, and surrounding businesses to make it all happen, as well as Ottobar’s security team, which ensured that everyone stayed safe. Hardcore pits can seem like a dangerous melee, but there’s an inner-circle code that usually keeps the disorder in check. Still, everyone knows so much could’ve gone wrong, right down to the weather.

“We were all just so unbelievably proud,” says Murphy. She and the band recall there being a sort of collective consciousness in the dell that day, from the first truck full of equipment through the final song that night. A few attendees even showed up the next morning to help clean up.

“That’s maybe, in a single day, in a single moment, the most connected we’ve ever felt to the city,” says Fang, who handed out high-fives and drumsticks before leaving the stage.

“And that’s kind of shocking. Because growing up, being here all the time, going to shows and playing Baltimore, and playing Baltimore again the next weekend, and then again the next weekend, it’s like you absorb this one place. But then you go on tour, and then years go by, and you kind of feel a little far, a little distant, from the community that you came from. You realize that you’re older, and there aren’t the same kids going to shows anymore, and the people that you used to see there have families now. So to come back in 2025 and play a show like that and have it feel like this actual culmination of our entire [lives]...”

He drifts off, almost lost in thought, then adds, “It sparked a lot that I’m personally still trying to process. But it definitely makes me want to be home even more.”

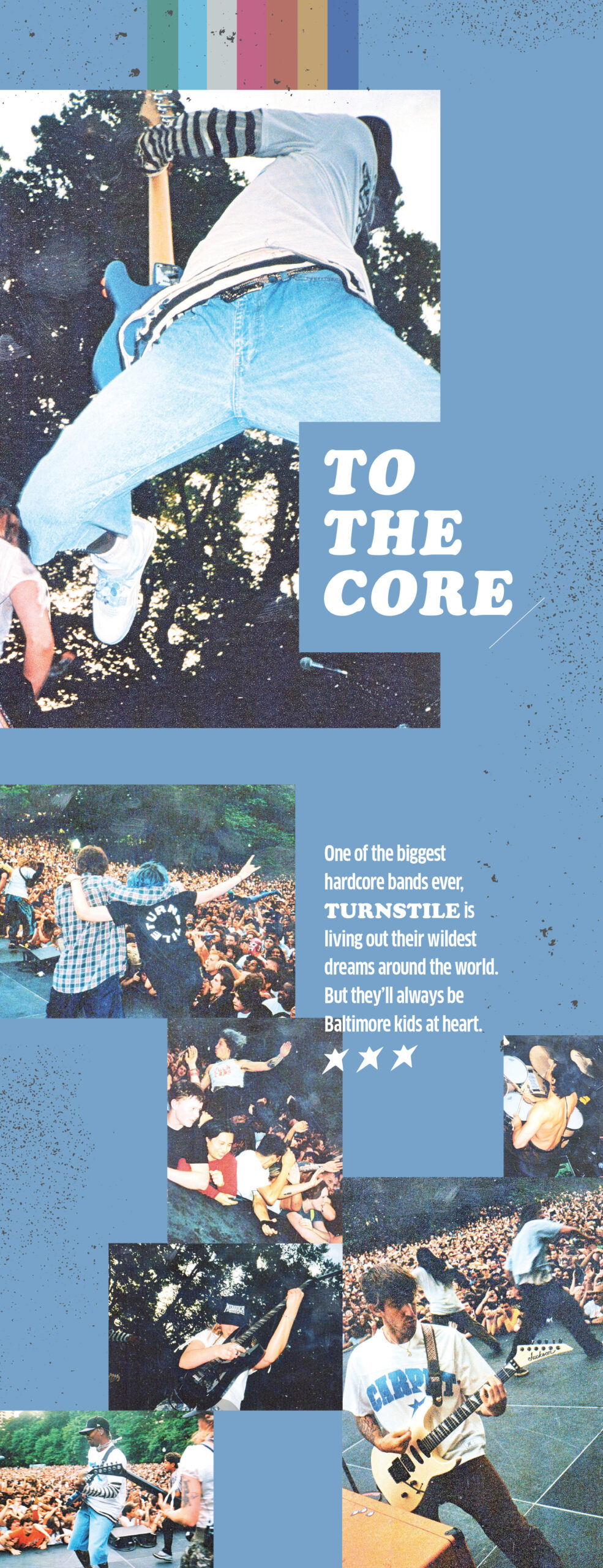

FROM LEFT: VOCALIST BRENDAN YATES, RHYTHM GUITARIST MEG MILLS, BASSIST FRANZ LYONS, DRUMMER DANIEL FANG, AND LEAD GUITARIST PAT MCCRORY. —ALEXIS GROSS

For Mills, the night took on its own meaning, it being her first official show with the band—after informally hopping in on the Blink tour, after meeting them across the pond years earlier, after being a fan even before that. However surreal, she felt truly welcomed. So much so, that at the end of the set, she took her very first stage dive.

“When I think back on it, I almost view it through the lens of everyone else that was there,” says Mills, who would be compelling with her cool nonchalance and wicked style even if she didn’t play a mean guitar. “Not necessarily as someone who was on stage playing . . . but every teenager, every kid, every small child who was there experiencing that, thinking how crazy it’s going to be for them to grow up and always have that as a formative experience.” (Google “Turnstile is for the kids” to see what she means—those little boys at Wyman were legends among us.)

Of course, every band comes from somewhere, but not all of them return this way. In July, they popped back into town for that Carpet Company drop. In Hampden, they painted a block of garages their signature rainbow colors, hung with friends and family, and met fans who spilled down Falls Road, signing their T-shirts and Never Enough vinyl like an old-school Tower Records release party, Baltimore-style.

Recorded at the iconic Laurel Canyon studio of producer-to-the-stars Rick Rubin, and featuring guest spots like Paramore’s Hayley Williams, this new album picks up where Glow On left off, unveiling a constellation of poignant, if not profound reveries that embody all that the band’s been through from then ’til now. (This includes Ebert’s departure in 2022. They don’t really talk about it, but on Instagram at the time wrote, “We are deeply grateful for our time together.”)

Yet while Turnstile has fully blown up, Never Enough seems to say: We’re still figuring it out. It’s an ongoing process, and an imperfect one at that. Time continues to be elusive, as the title implies. But each track is digging in, going deeper—attempting to capture some intangible feeling. At times, in the album’s wide-open spaces, they let themselves just sit with all of it. Always, though, at the core, they’re out there looking for a sense of connection, for something real, same as in those crowded pits years ago.

As for the future, who’s to say. But come what may, Baltimore remains a constant. And for that, it’s the star of their prescient music video for “Look Out for Me,” the album’s halfway mark. Directed by Yates and McCrory—the band is full of film buffs—this cinematic ode opens with a “Greatest City in America” park bench, then cruises around town in Lyons’ Volvo station wagon, picking up friends from rowhomes and busting a few doughnuts, before pulling up in the belly of Wyman.

At this point, the rip-roaring rager burns out into another Baltimore Club beat, beneath which a clip from The Wire drifts off into the ether like some kind of dream: “You promise? You got my back, huh?”

“When something is home, I don’t think that really changes,” says Yates. “As much as we’ll travel and spend time playing music to the depths of the world . . . Baltimore will always be home.”