Arts & Culture

Iconic Journalist Murray Kempton Had Baltimore Roots, But He’s Often Forgotten Here

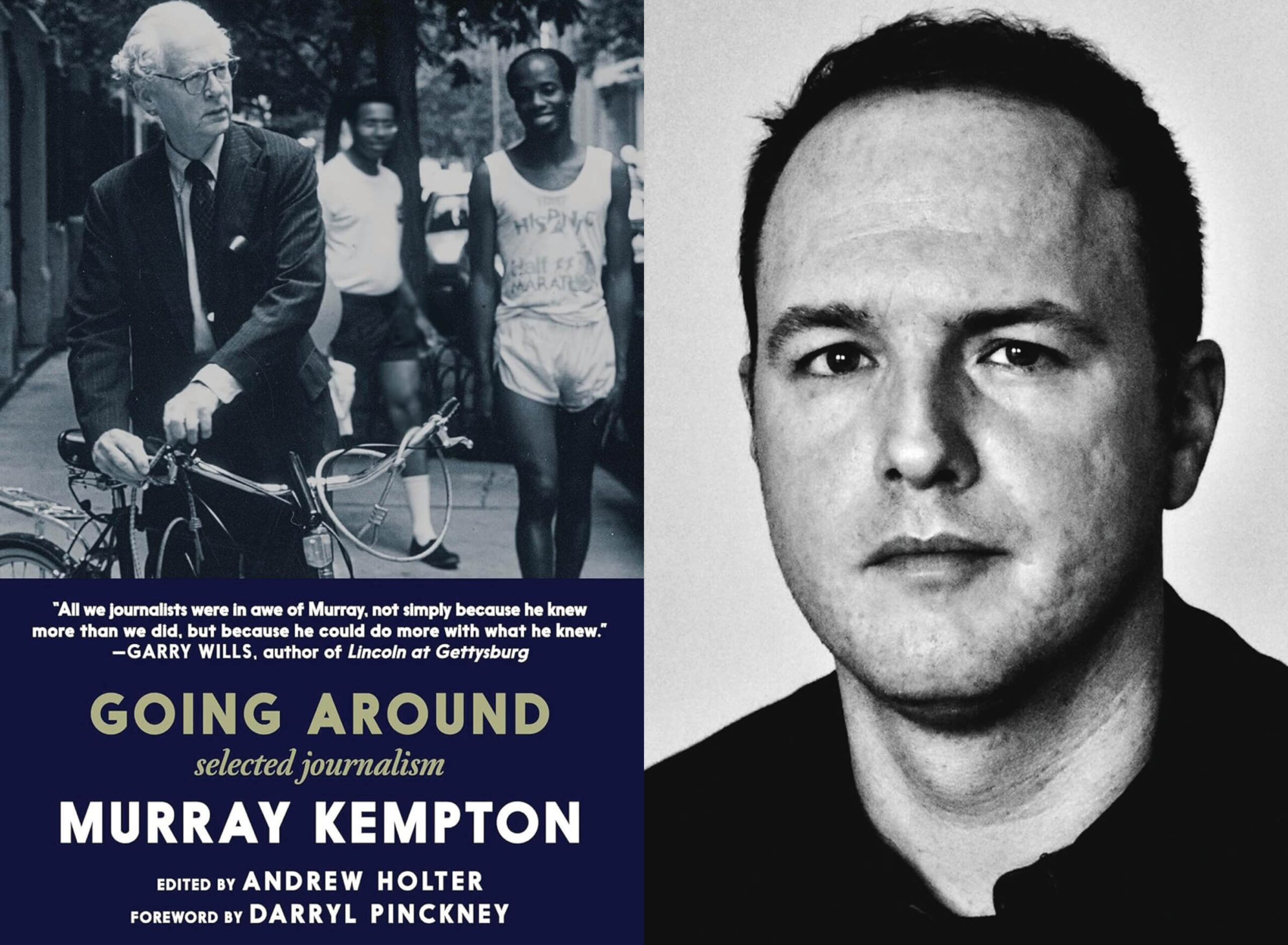

Maryland researcher Andrew Holter—who recently released an anthology of the Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist's work—discusses how Baltimore impacted Kempton's craft.

The sheer expanse of Murray Kempton’s career is difficult to wrap one’s head around. A former H.L. Mencken copyboy and Johns Hopkins News-Letter editor-in-chief, he eventually plied his trade as a columnist in New York. Writing from the 1930s through the 1990s, Kempton chronicled Roosevelt and the New Deal, the Big Apple of Trump and Giuliani, and seemingly everything in-between.

And now his columns are assembled in a new anthology. In Going Around: Selected Journalism, Maryland native, writer, and historical researcher Andrew Holter brings forth an edited collection of the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist’s work that feels as vital as the day it was written.

The epitome of a shoe-leather reporter, Kempton never learned to drive, typically moving from self-assignment to self-assignment by bicycle. But what he also brought was observation, perspective, moral clarity, and a literary eye to topics that remain as relevant as ever—subjects including white nationalism, police brutality, free speech, and the all-too-recognizable traits of authoritarians and their sycophantic enablers. Interested in some of the source material for recent films like The Trial of the Chicago 7, Oppenheimer, The Apprentice, and Conclave? It’s in this collection.

Below, we chat with Holter about Kempton’s upbringing in Baltimore, coverage of noteworthy Baltimoreans (from H.L Mencken to Tupac Shakur), and his unique writing style.

Granted, Kempton spent his career in New York. At the same time, he’s Baltimore born and raised—and completely forgotten here.

I found him while searching the 1930s and Nazi sympathy in Baltimore, particularly among German-American gentiles, for a City Paper piece in 2017. I’m a German American gentile from Maryland, so I was interested in that cultural history. I started looking into the atmosphere at Johns Hopkins in the ’30s, where Kempton went, and discovered his childhood home at Preston and Guilford was on my block. His family had been Confederate exiles, the people who were supposed to have run the Confederate States of America, and came to Baltimore after the Civil War. It was that cohort, that milieu in Mount Vernon, who were responsible for the Confederate statues that were taken down.

Kempton makes a name covering the Civil Rights movement. Coming from Baltimore provided a perspective his Northern colleagues didn’t possess, correct?

He [grew] up in this bizarre, hermetic world of privilege in Mount Vernon, but it was a privilege he called “shabby gentility.” Not true upper crust, but part of that society. His mother was a widow, and she was the only one of his school friends’ mothers who had a job. She worked at Hutzler’s. His family had a Black servant, and it was the Jim Crow era in Baltimore, but at Hopkins he fell in love with jazz and that world on Pennsylvania Avenue. He absorbs all of that and the quite radical ideas [percolating] on college campuses in the ’30s, and that gave him this different consciousness about social and racial inequality that he maintained for the rest of his life.

The breadth and depth of his experience, knowledge, and writing just staggers.

He’s the only writer who could write about H.L. Mencken and write about Tupac Shakur with first-hand insight, which is insane. He didn’t know Tupac personally, but he knew Afeni Shakur, Tupac’s mother [and former Black Panther], who lived on Greenmount Avenue briefly.

There’s an old line that I like about journalism being the first draft of history. This is the experience reading this book.

It feels like he knew everybody. One way to read this book is as an alternate history of the 20th century, through this particular path that Kempton took through it.

He obviously grew up reading Mencken, this towering newspaper columnist and national figure.

Mencken was the example of the shoe-leather reporter who becomes the brilliant cultural critic. He’s out reporting when he’s like 16, looking at murders every day, cutting his teeth, and then he also edited a literary magazine, publishing Theodore Dreiser, Zora Neale Hurston, and these people. That model, of the reporter who is also an intellectual, was really important. And then also Mencken’s sense of humor, which is totally there in Kempton.

There is also a dedication to craft.

I think he is one of the great unsung stylists. The most common criticism, from Tom Wolfe, was that he was “baroque.” His sentences could be challenging, but they were also entertaining. Personally, I would rather read something like that than something very plain, and it’s part of what makes Kempton worth reading. People don’t really write like he did anymore.