News & Community

Baltimore’s Last Pigeon Men

A tradition steeped in history, the city’s pigeon-racing culture remains alive, if not quite thriving.

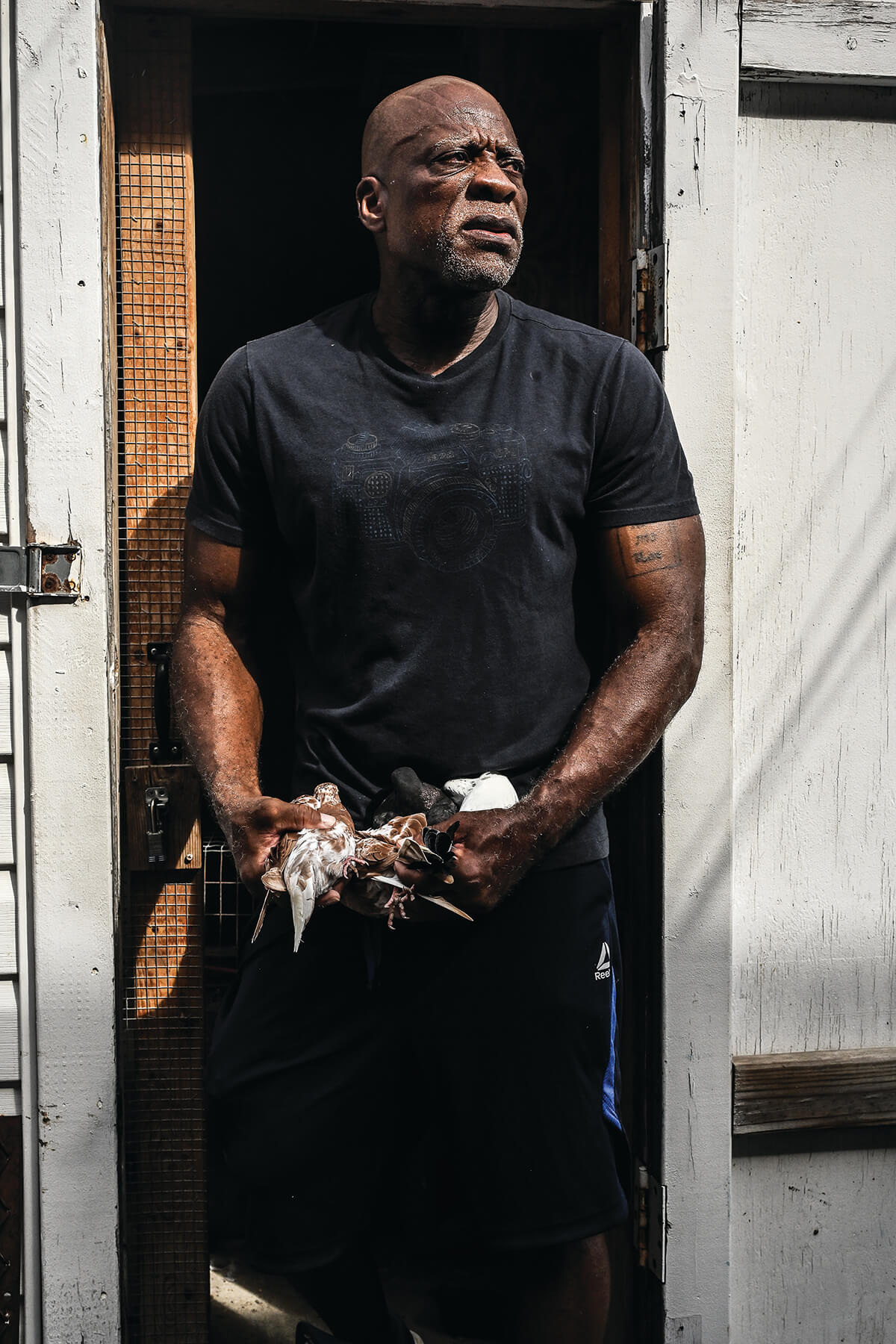

On a cloudy morning in April, Yul Foster steps out of a shed in his backyard with a pigeon in each hand. These delicate gray birds are the best in Foster’s loft, giving him the strongest chance at winning in the competitive flying season that starts in a few weeks.

His sweatshirt flecked with pigeon droppings, Foster explains that the pair of sisters he’s holding grew up in the same nest last year and only like to fly as a pair, which poses a problem, because it takes at least three pigeons to make a “kit” that flies together for competition.

“They’re in sync with each other,” he says. “They got the same pattern, the same wing beat.”

Foster cradles the pigeons gently, their feet dangling between his fingers and their wings tucked under his thumbs. They’re a dusky color that pigeon men call “dun,” sort of a faded version of the classic city pigeon you see pecking at crumbs on the sidewalk. Today he’s chosen a third young bird to try and keep up with the sisters in a training flight.

Shortly before noon, all three take off together, their powerful wings pulling them in big, looping circles over Foster’s rowhouse in Allendale. Foster stands in the center of his yard, his head tilted skyward. For the next few hours, we stand there together, our necks aching as the birds soar a thousand feet above us.

This is the life of a pigeon man—an increasingly rare breed in Baltimore these days, though their lofts once dotted alleys all across the city. Decades ago, Baltimore’s pigeon fanciers could take their pick of social clubs with dozens of members. Kids who were interested in pigeons hung around one of the feed stores in the city and eavesdropped on the older men to pick up pointers, and homing pigeon race results sometimes made the sports pages.

These days, a handful of small pigeon clubs are trying to keep the sport alive as it is battered by a resurgence of predatory birds, rising prices, and lack of interest from the next generation.

Foster, 63, is the central timer in a local pigeon club, so he organizes the flying schedule and trains his birds when he’s not working 12-hour shifts as a patient-care technician. He devotes precious weekends to the 80 pigeons in his loft and fellow members of the Baltimore United Tippler Club. But he’s not exactly optimistic when I ask about the future of the sport.

“We diehard pigeon guys, we don’t want to give up,” he says. “We want to hang in there just as long as we possibly can and keep going with it, because if it’s not us, there are no more younger people coming into the sport to keep it going.”

“WE DIEHARD PIGEON GUYS, WE DON’T WANT TO GIVE UP.”

Growing up near Johns Hopkins Hospital in the 1970s, it seemed everybody in the neighborhood had pigeons, Foster tells me. At 11 years old, he and friends began catching wild pigeons around Monument Street and keeping the birds in whatever they could find: first, a hollowed-out television set with a fan grate stuck on the front, then wooden fruit baskets from Northeast Market. Once, his mother caught him keeping pigeons in his bedroom.

“I was pigeon crazy,” Foster says.

He built something resembling a real coop when he was 13, after thieves came through and stole his pigeons out of a shoddy structure he’d been using to house them. (Pigeon theft was once a huge problem, fanciers tell me, though the issue sometimes resolved itself when perpetrators let their new pigeons out to fly and the birds followed their homing instinct back to their real owner’s yard.)

Foster studied books about pigeons at the Patterson Park library and used the money he made delivering The Baltimore Sun to buy birds from the famous old feed store at Fleet and South Ann streets in Fells Point. You could get a good starter pigeon for $2.50.

“It has to be in your blood,” Foster says. “It’s been with me since I was a little boy.”

Baltimore was well-known for its pigeon culture, and the pigeon men here were seen as experts in the sport, says August Hohman, who races birds out of a loft at his brother’s house in Baltimore County. Hohman’s father and uncles were pigeon men in Baltimore as far back as the 1930s, raising birds on Patterson Park Avenue. One of his uncles was the race secretary for the Monumental City Concourse Association, once the largest club in the city. That same uncle served in World War II and helped care for military carrier pigeons. Now 61, he still flies racing “homers” and keeps a variety of other pigeons with his brother.

Hohman and Foster, who grew up in the same neighborhood and have known each other since they were boys, often get together to “pigeon mumble,” the term for when pigeon guys get together to talk shop.

Hohman’s racing homers, as the name suggests, are trained to get back to their home loft as quickly as possible, sometimes flying hundreds of miles in just a few hours. On a race day, pigeons from different lofts are all released together from the same location—often in Virginia or further south, since race distances can range from 100 to 600 miles—and fly home, where an electronic clock records what time they got back.

Pigeons are incredible athletes, with lightweight bodies and prominent breast muscles that allow them to fly for hours at a time, sometimes reaching 60 miles per hour, without stopping. But it’s their ability to find home that has made them useful to humans for millennia.

Pigeons delivered the results of the first Olympic games in 776 B.C.E.; they helped Paul Julius Reuter establish his news service in 1850; and they saved hundreds of lives in World War I and World War II by flying messages through gunfire when radios failed.

The pigeon’s homing instinct has been sharpened over thousands of years of selective breeding, explains Verner Bingman, a professor at Bowling Green State University who studies animal navigation.

“Any bird is a good navigator,” he says. “What makes homing pigeons special is the depth of their fidelity to their loft.”

Pigeons are so attached to home they sleep on the same perch in their loft each night. And a good pigeon man knows where to find each of the birds in his coop, even in the dark.

How pigeons find home is a tougher question. It’s generally agreed that pigeons can identify directions, like north and south, using the position of the sun and the Earth’s magnetic field, according to Bingman. But to find home from the middle of nowhere, you also need to be able to figure out your position relative to where you want to go.

While there’s disagreement among experts about how pigeons do this, research has convinced Bingman that they parse different smells in the atmosphere to determine where they are and how to travel toward home. That smell “map” gets pigeons close enough to home that they can rely on a sophisticated visual map of the landscape surrounding their loft that they build over many flights.

The local, visual map allows Hohman’s pigeons to fly the distance from the former Key Bridge to his brother’s house in Rosedale in 20 minutes, for example. The smell map is how they find their way back to Baltimore during a race from Georgia.

“IT HAS TO BE IN YOUR BLOOD. IT’S BEEN WITH ME SINCE I WAS A LITTLE BOY.”

An hour into the training flight in April, Foster’s young pigeons are flying well. The sisters are sticking together and the third bird is staying with them, though starting to falter. It’s a good showing for their first flight of the year, Foster says.

“That’s the job as a trainer,” he tells me. “I have to get a third bird that’s on the same page as them.”

Foster’s focus has always been tipplers, a breed of pigeons slightly smaller than racing homers, whose primary strength is endurance—the duration they stay in the air—rather than distance or speed. Instead of racing home from hundreds of miles away, tipplers stay in the airspace near their loft and fly for up to nine or 10 hours or more while their owner and a contest judge watch from the ground below.

Suddenly, Foster sees something: “That’s the falcon,” he says, pointing at a fast-moving bird. “See him? That’s a predator.”

The falcon is heading in the same direction we last saw the sisters flying. “It might be going at them.”

There’s nothing he can do. And we can’t see the sisters. Hoping to at least bring home the third pigeon that broke off from the others, Foster releases a “dropper,” a plump white pigeon that the other birds have been trained to associate with feeding time. Once a tippler lands, it must be back in its loft within an hour or its flying time won’t qualify; the dropper signals it’s time to eat, encouraging the tippler to get home quickly.

We watch as the dropper and the third pigeon slowly make their way back to the loft, keeping half an eye on the sky for the sisters.

Peregrine falcons and Cooper’s hawks are the main threats to pigeons in the sky, and they are more abundant now than in recent decades, thanks, in large part, to the banning of the pesticide DDT in 1970s. But in raw numbers, there aren’t many falcons flying over Baltimore. Most likely, just a handful.

Still, predators are on the mind of every pigeon fancier who lets his birds out to fly. Some lose dozens of birds each season, which might explain why pigeon men talk about the local falcons like familiar antagonists.

Pigeon men see other new obstacles to the sport as well: The city began requiring pigeon coop permits in 2007 and limits the number of birds a fancier can keep to 125. There are also no feed stores in the city anymore, so pigeon men have to look elsewhere for the specialty supplies they use to keep their birds healthy.

Greg Campbell, the secretary of the Baltimore United Tippler Club, has tried to fill that gap by starting monthly Swap and Sell meetups near the entrance to the Baltimore Cemetery on North Avenue. Known as “Soup,” because of his last name, and also “the Professor,” because of his deep knowledge of pigeons, Campbell often wears multiple pieces of BUTC merch, including a hat with three pigeons on it that reads “Brotherhood, Featherhood.” There are also “Sisterhood, Featherhood” hats for women, he assures me.

Campbell talks with local pigeon men to gauge their needs and develop feed blends for their birds. Pigeons love dried peas, and their feed might also include safflower, wheat, or soybeans. Pigeon men carefully look after their birds’ health, giving them probiotics, administering vaccinations, and inspecting their droppings for signs of illness.

Despite a rep as “rats with wings,” pigeons are no dirtier than any other wild animal, and some studies have found they are resistant to avian flu.

Campbell’s loft in Lauraville is intensely organized. His pigeons are separated by lineage so that he can carefully choose the backgrounds of the birds he wants to breed. Some of his birds are descended from the loft of Harry Shannon, a celebrated Irish tippler man who died in 2019.

Like most pigeon men, Campbell knows the lineage of each bird going back generations (some still use notebooks to track family trees, while others now use specialty apps). He sells birds to other fanciers for $50 or more, depending on their breeding.

After a tour of Campbell’s loft, he sets up metal folding chairs in his driveway and we settle in to watch the tipplers he released that morning. Other guys stop by over the course of the morning to pigeon mumble, including talking a little trash and rehashing old pigeon-related grievances.

“It’s like being around a bunch of fathers,” says Clavon Smith, who at 40 is one of the youngest members of the BUTC. “They’re very knowledgeable. They keep you humble.”

Smith is trying to use social media to raise awareness of the sport today. He produces YouTube videos to promote BUTC, document Baltimore’s pigeon community, and teach others how he works with his birds. The club’s YouTube presence is a sign that even older pigeon men can adapt to newer times, Campbell says, and will leave a record of pigeon culture for the future.

“We might not be here no more, but somebody can look back years from now and see what these guys been doing.”

Across town in Curtis Bay, members of the Baltimore Pigeon Fanciers Social Club still host races and bird auctions in likely the last physical clubhouse for pigeon men in the city. Years ago, the club’s 70 or so members used the building as a social hall, complete with a bar and a kitchen that served burgers, shrimp, and crab cakes.

Now the bar sits empty, the walls covered in pictures of winning pigeons and the fanciers of the 1920s and ’30s, who stood next to their lofts in suits and hats for the photos. The club’s 20 members mostly stick to the garage now, where they meet to load birds for races.

On a Saturday in May, 91-year-old Ed Seitz was pleased to see one of his birds win a 150-mile race from Virginia, flying home at more than 60 miles per hour. Seitz has tried to get young people involved in the sport, but the technology now used to track homing pigeon races can be cost prohibitive. Kids today also have more activities vying for their attention than these men did as children.

“Back then, it’s all we had,” Seitz says.

That morning’s auction only lasted a few minutes, with most of the young birds selling for $35 or so. They’re still babies, with yellow down poking from under their adult feathers, and they let out shrill, indignant peeps instead of the coos of a more mature bird. The pigeon men assess each bird’s frame and lineage before deciding how much to shell out. One particularly good bird sells for $75.

Seitz, the elder statesman here, credits his longevity to his pigeons—though he noted, at 91, he is actually the second-oldest club member. The birds helped him stay active and got him through difficult times, including the death of his first wife.

“I think the pigeons have kept me going,” he says.

By the time I left Foster’s yard on that cool April training day, we had not seen the sisters in flight for more than an hour. Meanwhile, Foster kept shaking a small can of pigeon feed to tempt the dropper and the third pigeon back into the loft. He was concerned about the sisters, his two best birds, who seemed increasingly unlikely to come home.

“In this sport, you can’t have favorites,” he tells me sagely. “They’re the ones that break your heart.”

I go home, but only after making Foster promise he will text me if the missing birds come back. Throughout my interviews for this story, pigeon men have been gently encouraging me to buy a few birds of my own and get back into fancying. (I raised a small flock of pigeons as a teenager in my backyard in Pennsylvania.) But that night, it becomes clear that I don’t have the strength to be a pigeon man.

When Foster texts to let me know that the sisters never returned, I burst into tears.

“Please don’t feel bad,” he writes. “It’s part of our sport.”

This is why many people quit. But, Foster reminds me, there are also moments—almost miracles—that keep pigeon men coming back. The next morning, another text pops up on my phone. It’s a photo of one of the missing pigeons standing quiet on top of Foster’s loft, waiting to be let inside.

We’ll never know what she went through in the sky over Baltimore, or what happened to her sister, but she’s back.

She found her way home.