News & Community

when one of the locals overheard the bartender say that one of his patrons was going to swim the English Channel.

“Who? This big guy?” the Brit said, gesturing toward Pumphrey’s strapping, 6-foot-4, then-fiancé Joe Mahach. “He’s going to swim the Channel? That right?”

Mahach and Pumphrey’s friend Krista Mahler, an accomplished swimmer herself who had just arrived in England for support, turned and pointed to the 5-foot-5-1/2 Pumphrey, who looked like she could still be in college.

“Nope. I am,” Pumphrey said.

“Oh, she’s too small," the British man responded, dismissively.

“No, it’s less resistance,” an older woman piped up from a few seats away, adding with encouragement, “Fucking slaughter it.”

“The call” had come a few minutes earlier as Pumphrey and crew were contemplating another round. She saved the screenshot—1:59 p.m. Her boat captain wanted her to launch at 2 a.m. that morning. She and her team—Mahach, Mahler, and her father, Jack—had expected a later start, based on projected tide and weather conditions, possibly Saturday or Sunday, certainly not in 12 hours. “I immediately started crying and shaking with fear,” Pumphrey recalls. Then, she went back to the hotel, organized everything she needed, and tried to sleep.

By 3 a.m., she was in the boat with her team, the captain, and a rules observer—because there are lots of rules regarding swimming the English Channel. For example, though water temperatures hover around 60 degrees, wet suits are a no-go. Only a swimsuit, cap, goggles, earplugs, and nose clip, if desired, are allowed.

Swimmers must start on the natural shoreline and can’t touch the boat during their swim, even when refueling with electrolytes and carbs. They have to remain visible at night with light sticks, and both the captain and official observer have authority to pull a swimmer because of health safety concerns.

The challenge presented by the English Channel is beyond daunting. Since 1885, when British merchant seaman Matthew Webb first crossed the 21 miles from Dover to Cap Gris-Nez, France, igniting interest in the swim, a little more than 2,000 individuals have successfully followed in his wake. By comparison, that’s a fraction of the 7,000-plus who have ascended Mount Everest.

“When the boat gets within 10 minutes of the start, the captain, who is holding a tiny flashlight, tells me, ‘You’re going to jump in, swim a couple hundred yards to the shore, raise your hands, and that will begin your swim,’” recounts Pumphrey, a painter by profession, in her Greektown studio. “Staring into that dark cold water and jumping in, that was the scariest moment I have ever experienced. I stood on the rocks with the white cliffs of Dover towering, shining over me, already numb from the cold, and I say out loud to myself as I raise my arms and wave three times to signal the start, ‘This is what you’re doing today. This was your idea.’”

It gets worse from there, obviously. The channel waves batter her, pushing her arms aside as she struggles to maintain her stroke. It’s so dark, there is no visible horizon line. She loses all sense of direction in the tumult, and begins vomiting. Tears come. A massive jellyfish stings her stomach and she panics briefly, believing it is stuck inside her suit. Once morning breaks, Mahach, a former water polo player, dives in and swims alongside her for a stretch to steady her nerves, which is allowed as long as he doesn’t touch her.

Fourteen hours and 19 minutes later, she climbs out of the water. In France.

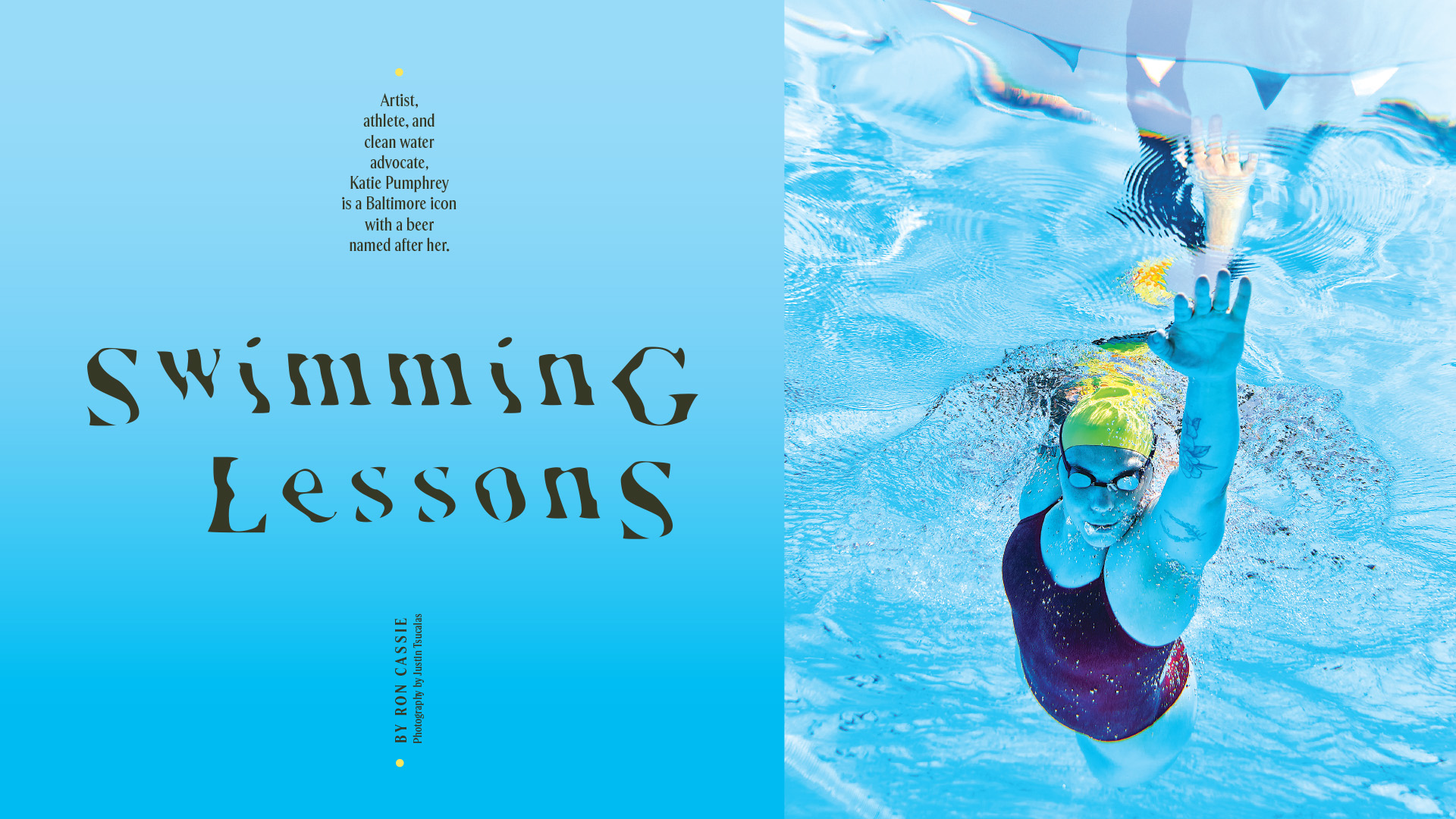

Katie Pumphrey swimming from Fort

McHenry to the Inner Harbor in May. OPENING

SPREAD: Underwater photo of Pumphrey training at

the Coppermine Meadowbrook aquatic center.

NOW 37, KATIE PUMPHREY has swum the English Channel three times. She did it again in 2022, and completed her third attempt on July 30. Her other major swims include a 28.5-mile circumnavigation of Manhattan Island and two 20-mile Catalina Channel voyages, which, along with the English Channel, make the Triple Crown of open water swimming. Pumphrey is the 194th person and 73rd woman ever to accomplish the feat.

When not training or coaching other endurance swimmers—she had several mentees with her for the Great Chesapeake Bay Swim in June—Pumphrey is a Maryland Institute College of Art-trained visual artist, whose work has been widely exhibited. Both her large-scale canvases and more whimsical sculptures are deeply connected to her open water experiences. Her typical palette, not surprisingly, includes swaths and shades of blue. Her blending of abstract and figurative images often intertwines personal and environmental themes.

More recently, she has incorporated historical references. In fact, an upcoming solo exhibition at the Creative Alliance titled “Swimming Pool” features two new works based on famous water-themed paintings. One is a massive reworking of the 1851 “Washington Crossing the Delaware” by German painter Emanuel Leutze, and the second is a re-imagining of “Watson and the Shark,” a 1778 oil painting by Anglo-American artist John Singleton Copley, which depicts the rescue of a teenage boy off the coast of Cuba after a shark had bitten off half of his leg. (Ironically, while Pumphrey can get anxious about predators during swims, Jaws is also a favorite movie.)

Last year, however, she added another dimension to her CV. Highlighting the Waterfront Partnership’s decades-long campaign to restore Baltimore’s post-industrial harbor, Pumphrey conceived a first-of-its-kind, 24-mile swim from the Bay Bridge into the city. Since that effort—nothing short of heroic, but also visionary—Pumphrey has become a leading figure in the ongoing push for a swimmable, fishable harbor, including joining last summer’s “Harbor Splash,” a buzzed-about public swim that was scheduled to be repeated this summer, but was ultimately cancelled due to weather. In late June this year, Pumphrey keynoted the first-ever Swimmable Cities conference in Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Her most endearing quality isn’t her prodigious swimming skills or talent for painting, however. It’s her Charm City unpretentiousness and simple wish to bring people together in a common cause. Greeted by a cheering crowd, which grew louder as she reached Harborplace’s docks after her 14-hour, Bay Bridge to Baltimore journey in 2024, the sunburned swimmer took a single deep breath and smiled and asked, “How you guys doing?”

As Pumphrey is quick to acknowledge, she has faced a multitude of obstacles, physical and mental, some anticipated, some not, as she has taken on the seemingly impossible over the past 10 years.

It is kind of the point. No one swims the English Channel without learning a few things. It’s a test of character and will, but the experience also has a way of putting one’s journey into perspective. As Sir Edmund Hillary, the first climber along with Sherpa mountaineer Tenzing Norgay to reach the summit of Everest, once said, “It's not the mountain we conquer, but ourselves.”

Katie Pumphrey painting her massive

reworking of “Washington Crossing the Delaware” by

German painter Emanuel Leutze.

THE THINGS YOU LOVE AS A CHILD, YOU’LL ALWAYS LOVE.

“We had an above-ground swimming pool in our backyard,” recalls Jack Pumphrey, during one of his daughter’s recent harbor swims. “None of the older kids [two brothers and a sister] showed much interest, but any time after work or after dinner in the summer when I wanted to cool off, she’d get in with me, even when she was small.”

Pumphrey calls swimming her first love. Her favorite animal as a girl was a penguin (still is). She started swimming competitively starting at 5 years old, later joining the Monocacy Aquatic Club in Frederick, and becoming a standout at Middletown High School. Art was there early, too. “They’ve always been connected,” she says. And when she was deciding about college, she chose to commit to art over offers to swim collegiately, attending MICA. “One of the best painting programs is right here in Baltimore. It was the best choice for me, and I fell in love with this city.”

Still, she kept returning to swimming, working as a lifeguard and giving lessons at the 33rd Street YMCA around her classes. She was not a "gym person” when she was young but always someone who liked to work toward a goal. After graduating in 2009, she signed up for the 4.4-mile Chesapeake Bay Swim—ambitious for a first long-distance, open water swim—and had an epiphany.

“I’m not a land animal,” she jokes. “I’m a sea creature.” Her first words upon climbing from the water were, “I want to do that again.”

The next year, she did, as well as the 7.5-mile Potomac River swim in Southern Maryland. She loved that even more. Not only the distance, but the teamwork: Each entry receives kayak support for that swim.

By 2013, she was becoming enamored with the idea of the crossing the English Channel. “I thought, if I was going to go for a big swim, I should go for the mother of them all.”

her upside-down pool

floatie sculpture hanging over her dog, Adja.

THERE IS A CRACK IN EVERYTHING, THAT'S HOW THE LIGHT GETS IN.

When Pumphrey was 9, she began experiencing symptoms of chronic pain, a condition that would mystify and frustrate her into her mid-20s. Despite years of visits to doctors and physical therapists, with regimens of painkillers, anti-inflammatories, and anti-seizure drugs, nothing provided lasting answers or solutions.

She felt powerless at times—hopeless, too. Coaches sometimes doubted what she experienced was real. Nonetheless, she managed to swim, run track and cross-country, captaining her varsity teams and earning All-County honors. Through cross-country—swimming was more of a sprint shorter—she discovered something counterintuitive. Intense endurance workouts brought a measure of relief.

Effective treatment for chronic musculoskeletal pain remains notoriously elusive. But backing up her experience, a growing body of evidence has shown aerobic exercise—which produces endorphins, the opioid neuropeptides central to pain relief, pain perception, and stress responses—can provide benefits. Swimming, in other words, became both purpose and pain management.

It’s tough medicine: in the off-season, three to four days a week in the pool; 25,000 to 30,000 yards of interval training and drills. In the spring buildup, four to six days in the water, 40,000 to 60,000 yards. Plus, physical therapy twice a week. One visit to spur recovery with massage and cupping and other therapeutic techniques. The second, more preventive, to strengthen areas of weakness.

It’s not a cure. But ultra-marathon swimming has provided Pumphrey with a sense of control over what she sometimes refers to as “my old friend.” She can distinguish the pain and soreness from swimming from the chronic pain and greatly prefers the former. “At least,” she says, “there is a good reason for the pain. It puts into the back seat what had been in the front seat.”

Meanwhile, during her open water swims she has developed other “strategies” like singing—and telling corny jokes during nutrition breaks—to keep the demons at bay. “The rule,” she reminds her team before every swim, “is everyone has to laugh at my jokes.”

Pumphrey prepares to

jump in the water before a recent

Inner Harbor swim.

INSPIRATION EXISTS, BUT IT HAS TO FIND YOU WORKING.

“I hate that word, muse,” Pumphrey says, crinkling her nose, while also acknowledging, that yes, open water swimming has obviously become her muse as a creative artist. “It sounds like waiting for lightning to strike. When you’re an artist, you get started.”

Whatever her semantic objections, something inexorably changed amid the turbulence of the English Channel. Prior to that epic swim, Pumphrey’s work at MICA explored topics like family and memory. After graduation, she turned to figurative painting of things in motion: large animals, runners, and the like. But that swim proved much more than a physical test of stamina and derring-do (more than half of all attempts fail), it was a profoundly emotional and life-changing event that, to an extent, was impossible to anticipate. “What happened after that swim,” she says, “was I wanted to make paintings as powerful as that experience.”

Initially, Pumphrey shifted toward the abstract blue paintings for which she is recognized. A Washington Post review of Pumphrey’s 2023 “Monsters Below” show characterized the “abstract aquatic vibe” of her “oceanic art” as evoking “both exhilaration and danger.” It’s an apt description of much of her work, including her reworkings of “Watson and the Shark” and “Washington Crossing the Delaware.”

“There are times your personal experience as an artist comes into your work, but that’s not the ‘subject’ of my painting,” she says. “There are areas of chaos, including allusions to imaginary sea creatures and ‘washing machine’ waves in my paintings, and then also blocks of color and calm that are related to my swims. I think of them though in terms of anxiety and fears, the repetitive cycles we all go through. We find a way through those things, which can be imaginary, too, and steady ourselves again, right?”

It can be heavy stuff, but in keeping with her personality—“Don’t make me look too serious, that’s not me,” she chided a photographer recently—she also brings bright colors and a spirit of joy to her work.

Taking a selfie

with other swimmers at this summer's

Harbor Splash preview event.

FIND A GOOD PARTNER

Standing on the bow of the boat during her swims, Joe Mahach, Pumphrey’s husband, crew chief, “feeder”—and support swimmer—is so simpatico with his wife, it’s difficult to come up with an analogy in sport. A swimmer growing up in the surfing destination of Santa Cruz, he understands cold water and big waves. He earned his B.A. in international studies at the California State University Maritime Academy, while acquiring some maritime sea and boating skills. When they met, both were teaching swimming in Canton and seeing other people. “We went on double dates, just not with each other,”

Pumphrey says. “We were friends first. That was important. After those relationships broke up, and we are still all in touch, it set up this great partnership.”

A former Peace Corps volunteer in Togo (their lovable dog, Adja, is named for the village where he served) and Baltimore schoolteacher, Mahach is as warm and unassuming as Pumphrey, with whom he shares a wacky sense of humor and appreciation for Baltimore kitsch. They’re so normcore and proudly nerdy, they host the BmoreTrivia night at The Dive, a corner bar near their old pool. If you’ve seen Nyad, the award-winning biopic about the combative relationship between controversial, prickly, self-absorbed endurance swimmer Diana Nyad and her best friend/ fitness coach Bonnie Stoll—their joint vibe is the exact opposite.

“Joe was the first person who I told about my crazy idea to swim the Channel,” Pumphrey recalls. “We weren't even dating yet.”

“I can’t remember my exact words—I know it was after a masters swim team practice,” Mahach says. “But it was something like, ‘Hell yeah!’ I knew how much training she was capable of. We began dating along the way and two years later were in the boat together.”

“I think we both thought dating was either going to ruin our friendship or we’d end up married,” Pumphrey says. “We knew we were in love pretty quickly.”

In hindsight, swimming the English Channel, discovering her voice as a painter, and falling in love with her life partner happened, inexplicably, all at once.

“When I say swimming has given me everything,” she says, smiling, still surprised by the tidal shift, “I mean it literally.”

Katie

Pumphrey's "Big Swim" beer by

Peabody Heights Brewery.

MAKE IT SUSTAINABLE AND CREATE COMMUNITY.

“When we announced the first Harbor Splash in 2023, Katie was the first person who called us,” recalls Adam Lindquist, director of the Healthy Harbor Initiative at the Waterfront Partnership. “We got together for coffee. I knew who she was, this accomplished artist and endurance swimmer, and the first thing she says to me is she’s been dreaming of swimming in the harbor for years, and not by herself, but with a lot of people. Remember, there was a great deal of skepticism about swimming in the harbor.” (There still is.)

The work continues, but Baltimore has made great strides in improving the water quality of its crown jewel after the Healthy Harbor Initiative’s launch in 2010. Eight years ago, the city approved a $1.6-billion plan to rehabilitate the municipality’s aged sewer system and stop overflow wastewater from leaking into the harbor. Over the last 11 years, four trash wheels—strategically placed at the mouths of Jones Falls River and Harris Creek, for example—have prevented five million pounds of garbage from entering the harbor. Floating wetlands and 1.5-million water-filtering oysters have been planted.

Pumphrey in many ways has superseded the first “Mr. Trash Wheel” as the celebrity face of the Healthy Harbor Initiative. Peabody Heights Brewery named a beer in her honor. Her 24-mile Bay-to-Baltimore swim did not just draw an enthusiastic crowd, it garnered international attention, highlighting the progress the city—long the poster child of post-industrial blight—has made in reclaiming its waterfront.

It also demonstrated the potential for recreational water sports. Just this summer, Pumphrey and Mahach launched a nonprofit, Baltimore Open Water Swimmers (BOWS), to bring more open water events to the harbor—1- or 2-mile races—and attract other ultra-marathon swimmers to an annual Bay-to-Baltimore swim.

It was in recognition of the impact of this particular, groundbreaking swim that Pumphrey was invited to keynote the firstever Swimmable Cities conference, a global, grassroots initiative inspired by the Paris Olympics to champion the right to swim and urban swimming culture.

“The Waterfront Partnership [a nonprofit] was one of the first signatories to the Swimmable Cities charter,” Lindquist notes. “More than 120 organizations and 72 cities have signed on, but Baltimore City has not. We’re working on that. The mayor jumped in the harbor with us last year.”

RESILIENCE IS NOT A TRAIT, IT'S A PRACTICE.

Accounting for temperatures, tides, and weather, the window for Pumphrey’s second Bay-to-Baltimore swim this year was May 18 to May 23. Water temperatures for last year’s late June 24-mile swim had reached 83 degrees, leading her to the brink of heat exhaustion.

On May 19, the night air hovered around 50 degrees. The water, in the mid-60s. “You couldn’t pay me to jump in,” one of Pumphrey’s two older brothers commented to the other as they ducked the wind and splashing water on a support boat, out of earshot from their sister. More disconcerting, the winds remained unexpectedly strong.

Diving into the Bay at Sandy Point State Park in Annapolis, Pumphrey—lit by green neon glow sticks tied to her swimsuit—got off to a solid start. Her support boat, not so much. It struggled to maintain a safe distance in the white-capped waves, bouncing too close to Pumphrey at moments, too far away at others.

“How do you feel about your safety?” the captain of the main boat asked the captain of the second boat over the radio. Pumphrey was handling the chop better than the boats. “I don’t know,” came the response. Forty-five minutes into the swim, Mahach and the captains called off the attempt—largely for her team’s safety.

It was the second time that one of her notable open water swims had been aborted. The first was a 15-mile swim off Long Island because too many participants and support kayaks were struggling in similar rough conditions. That she possesses natural talent as a swimmer and endurance athlete goes without saying. Her whole family is athletic. The deep desire—need might be a better word—to tackle such daunting physical challenges is a different thing. As is the ability to suffer through fear, fatigue, and pain. Maybe it’s a quality best described as an inability to quit when the going gets tough.

It’s a paradox, but trauma, specifically childhood trauma, is often linked to top endurance athletes, who also have been shown to be at higher risk for anxiety, depression, and substance abuse. Their chosen sport may be, in essence, a successful coping mechanism. “Chronic pain,” Pumphrey says, nodding, adding some of her coaches called her a “slacker” as a kid.

Either way, she’s not 100-percent sure of the source of her “battery power.” What she knows is swimming “is what makes me tick.”

Still, it’s hard to account for the determination to push through waves that bat her arms down. Through chills, vertigo, nausea, dehydration, and jellyfish stings so harsh they leave marks that last two months. Past sexist naysayers who make rude remarks about her body and say things like, “Who tricked you into doing this, honey?”

Not that it is all bad by any means. There is nothing like the sun coming up a few hours into a swim or seeing a pod of dolphins in the depths beneath her, which happened off Catalina Island in Southern California.

In the case of the Bay-to-Baltimore swim, there has been the fear of letting people down and failing in her mission to promote urban swimming. Which is why she picked herself up after May’s aborted swim and swam the last leg later that morning—2.4 miles from Fort McHenry to Harborplace—to meet the gathered crowd and demonstrate once again the Inner Harbor, most days, is now swimmable.

But there is another reason, too, simpler, more visceral, that may explain her wherewithal to persevere. “I think I’m more afraid of not finishing a swim,” she says, “than the pain of finishing it.”